Modified immune Tregs show promise in treating lupus nephritis

Novel treatment aims to work without suppressing immune function

Written by |

Modified anti-inflammatory T-regulatory immune cells, known as Tregs, were able to suppress autoimmune activity in cells and in a mouse model of lupus nephritis, a common complication of lupus marked by kidney inflammation, a new study reports.

These findings support the development of a Treg-based treatment that uses a patient’s own cells to prevent lupus-related autoimmune activity without suppressing immune function.

“The ability to target, specifically, the disease-causing immune defect, without the need to suppress the entire immune system, is a game-changer,” Eric Morand, MD, PhD, the study co-lead and the dean at Monash University’s Sub Faculty of Clinical & Molecular Medicine, in Australia, said in a university press release, also calling the results “profound.”

While the effects to date “are only medium term, we are confident the treatment can be easily repeated as needed,” said Morand, also the founder of the Monash Lupus Clinic at the university.

The study, “Smith-specific regulatory T cells halt the progression of lupus nephritis,” was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Scientist develop method to create specialized Tregs

The study’s results, while preclinical, were welcomed by the lupus patient community in Australia.

“This new treatment will really help people living with lupus; if the treatment was around 30 years ago it would have made a real difference for me,” said Vu Nguyen, a 39-year-old woman with lupus who was diagnosed at age 9.

“It could really cut down the many different types of medicines we take. With this procedure, we could possibly need just one treatment,” said Nguyen, who founded the nonprofit Lupus Victoria, which raises money for research for a cure.

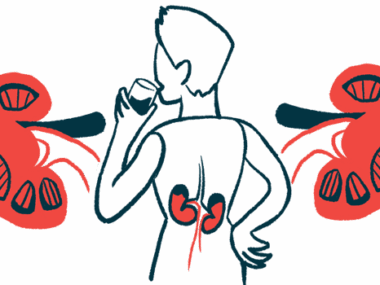

Lupus nephritis is a severe complication of lupus marked by kidney inflammation and damage. Standard treatments include immunosuppressants and anti-inflammatory medications that aim to control autoimmune disease activity.

Tregs are a type of immune cells with anti-inflammatory properties that promote immune self-tolerance and prevent autoimmune diseases. Defective or decreased numbers of Tregs have been implicated in the development of autoimmune diseases, including lupus. As such, Treg-based approaches to suppress autoimmune activity have been considered as potential treatments for these disorders.

Now, a team of researchers led by Morand and colleagues at Monash has now developed a method to create specialized Tregs with the potential to restore immune self-tolerance and prevent autoimmune attacks in people with lupus nephritis.

Targeting Smith antoantigens in new treatments for lupus

Many people with lupus test positive for self-reactive antibodies, or autoantibodies, that target Smith autoantigens, a family of RNA-binding proteins found in most healthy cells. In fact, the risk of disease flares is more than three times higher in lupus patients who test positive for Smith autoantibodies, a name derived from a lupus patient named Stephanie Smith who was diagnosed in the 1950’s.

In turn, the presence of these autoantibodies is also linked to certain genetic variants in HLA genes — the primary genetic risk factor related to autoimmune diseases. These genes encode immune cell proteins that help the immune system distinguish so-called self healthy parts of the body from non-self ones, such as invading microbes or cancer.

The team first screened and identified fragments of Smith proteins that bound strongly to an HLA protein encoded by a variant of the HLA-DRB1 gene, called DRB1*15:01 (DR15). This variant is an established genetic risk factor for lupus. Using immune cells from a healthy HLA-DR15-positive donor, T-cells that bound strongly to the top-binding Smith fragment, via T-cell receptor proteins (TCRs), were selected.

Using a harmless lentiviral vector, isolated human Tregs were then genetically modified to produce these “healthy” Smith-specific TCRs. Cell-based tests confirmed the modified Tregs were stable, functionally active, and able to suppress autoimmunity.

The researchers then used the method to modify Tregs obtained from lupus patients who tested positive for Smith autoantibodies and carried the HLA-DR15 variant, called Smith Tregs. After incubating the top Smith fragment with immune cells to elicit a lupus-like autoimmune response, the addition of Smith Tregs suppressed autoimmune activity.

The levels of immune signaling proteins also were affected. Levels of the anti-inflammatory protein interleukin-10 were higher, and the levels of pro-inflammatory interferon-gamma and interleukin-17A, which are particularly elevated in lupus nephritis, were lower.

The Smith Tregs were able to restore lupus-related deficiencies in Treg function and re-direct their responses to target lupus autoantigens.

Treatment found to ‘competely arrest’ lupus kidney disease development

The therapy then was tested in immunocompromised mice that were injected with immune cells derived from a lupus patient and the top Smith fragment. These mice eventually developed impaired kidney function and damage.

At the onset of kidney injury, the mice were treated with Smith Tregs, which suppressed disease activity significantly better than patient-derived control Tregs. At the same time, protein levels in the urine remained relatively low in mice given Smith Tregs, but increased over time in control mice, a sign of disease progression.

Tissue analysis also revealed that the extent of kidney damage in mice given Smith Tregs was significantly lower when compared with control Treg mice.

“We showed the effectiveness of this approach using human lupus patient cells, both in the test tube and in an experimental model of lupus kidney inflammation,” said Joshua Ooi, PhD, a study co-lead who heads the Monash University regulatory T cell therapies group.

“We were able to completely arrest the development of lupus kidney disease, without the use of the usual non-specific and harmful immunosuppressant drugs,” Ooi said.

That the therapy uses each patient’s own cells “is a very special part of this,” Ooi said.

“It’s like a reset of the abnormal immune system back to a healthy state — kind of like a major software upgrade,” Ooi said.

We showed the effectiveness of this approach using human lupus patient cells, both in the test tube and in an experimental model of lupus kidney inflammation. … We were able to completely arrest the development of lupus kidney disease, without the use of the usual non-specific and harmful immunosuppressant drugs.

This new Treg method has the potential to treat various other autoimmune diseases such as diabetes, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, myasthenia gravis, Sjögren’s syndrome, and scleroderma.

“This breakthrough offers huge hope not only in lupus but across the spectrum of autoimmune diseases,” said Peter Eggenhuizen, a PhD candidate at Monash and a co-first author of the study, who notes that “there is a huge range of autoimmune diseases that could be targeted with this approach.”

Rachel Cheong, a former PhD candidate at Monash and also co-first author of the study, noted that the treatment must first be personalized to each specific autoimmune condition.

“The great thing is that because the treatment is very specific, it doesn’t harm the rest of the immune system. However, this means that the treatment needs to be carefully developed disease-by-disease, as each one is distinct,” Cheong said.