Study Yields Interesting Findings About Molecular Development of B-cells in SLE Patients

Written by |

B-cells in people with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are distinct from those in healthy people, even at very early stages in B-cell development, a new study shows.

The study with that finding, “Epigenetic programming underpins B cell dysfunction in human SLE,” was published in Nature Immunology.

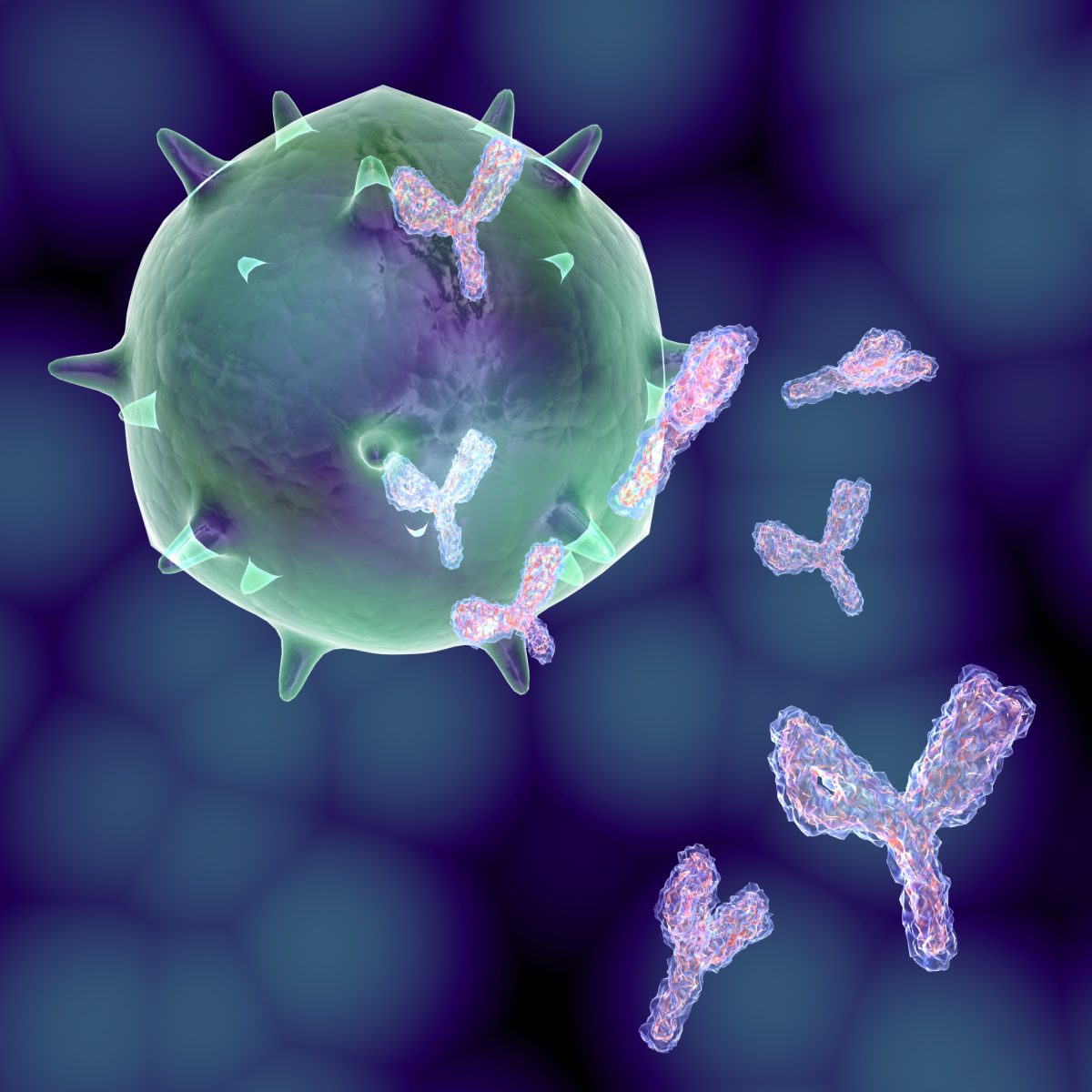

B-cells are the immune cells that make antibodies, including the self-reactive antibodies that are characteristic of SLE. As such, these cells play a central role in SLE development, and understanding just how — and why — they behave differently from B-cells in healthy people is a central goal of modern research.

Researchers collected blood samples from nine individuals with SLE and 12 individuals without it; all of the study participants were African American and female.

The researchers then analyzed B-cells from these patients. Specifically, they looked at the cells’ transcriptomes (what genes are being “read”) and epigenomes (how DNA within the cell is “packaged,” which directly affects how genes are read).

This analysis looked at a variety of subsets of B-cells — that is, cells expressing different markers that are indicative of different stages and specialized functions of B-cell development.

Detailed results of this analysis get rather technical rather quickly, but from a very general perspective, the researchers identified transcriptome and epigenome features that were distinct in B-cells from people with and without SLE across all the subsets analyzed.

One of the more interesting findings of the study was that these differences were found at all in “resting naïve” B-cells. That’s because once an individual B-cell has matured, it basically wanders around the body until it comes in contact with an antigen, a molecular signature that the cell recognizes as a threat (although, in SLE, the “threat” is the person’s own cells, which is the problem).

Once it finds an antigen — and with the help of other immune cells and signals — the B-cell can become activated, making antibodies to fight the threat.

B-cells in the aforementioned wandering state are “resting naïve” because they aren’t activated (resting) and haven’t yet seen an antigen (naïve). The new study showed that even these cells, at a relatively early stage of B-cell development, were different in people with and without SLE, in terms of their transcriptome and epigenome.

This, the researchers wrote in their paper, suggests these cells “may have been exposed to disease-inducing signals,” but further research will be needed to figure out exactly what those signals might be. Additionally, the results will need to be validated by future studies that include more people.