New Way to Record a Key Nerve’s Signals Could Improve Lupus Treatment, Study Reports

Written by |

New York scientists have come up with a new way to measure electric signals in the major nerve running from the head to the abdomen — a discovery that could improve diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory diseases like lupus.

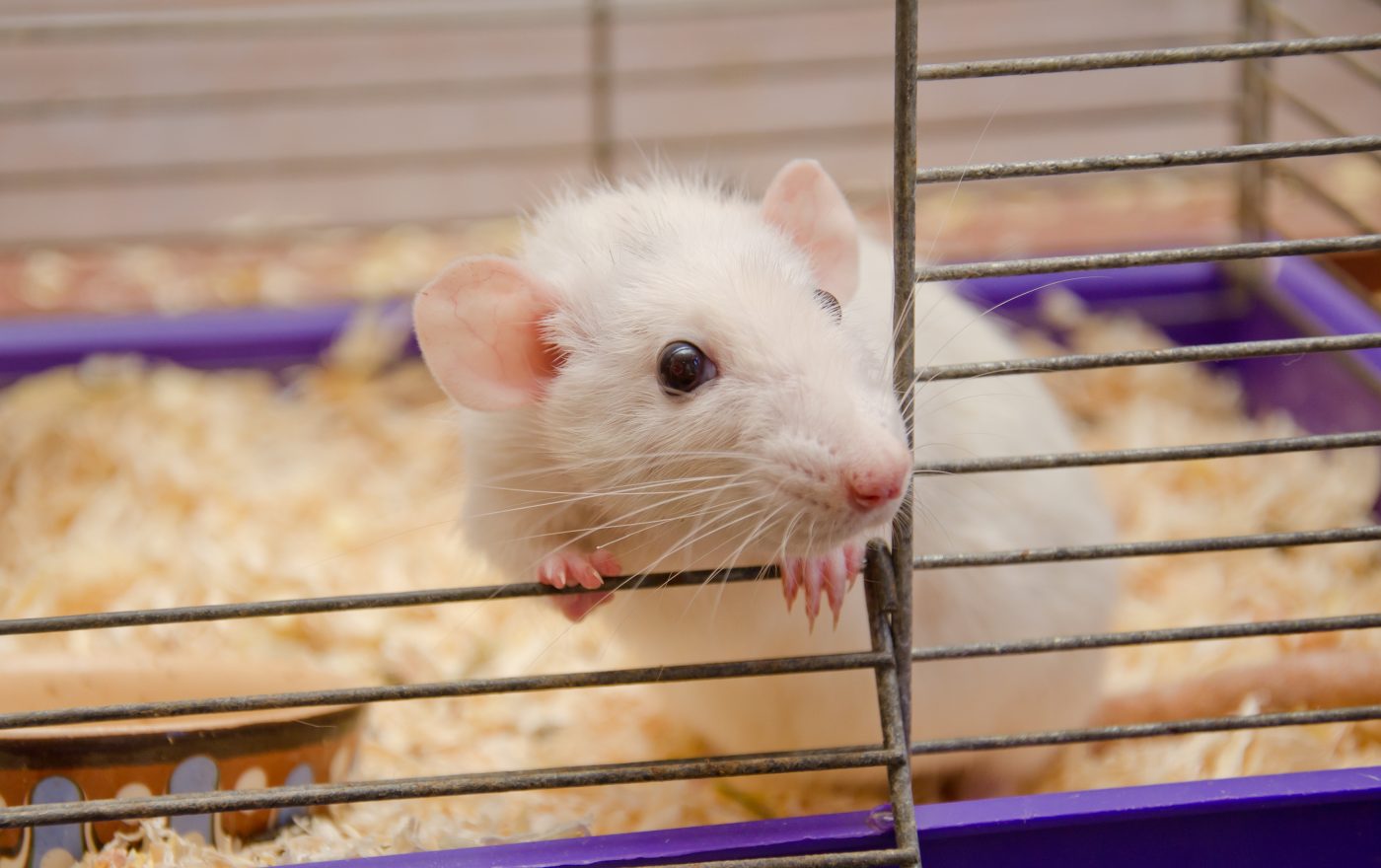

The team at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research used mice to do the vagus nerve study.

Their research, “Standardization of methods to record Vagus nerve activity in mice,” was published in the journal Bioelectronic Medicine.

The vagus nerve is the longest in the autonomic nervous system, the part that controls internal organs and glands. The organs it covers include the pharynx, larynx, heart, esophagus, stomach, and bowel.

Scientists say the way it controls organ function is by transmitting information about inflammation and injury back to the central nervous system.

Researchers wondered if selective activation of the nerve could serve as a monitoring system to assess the body’s inflammatory response in real time.

Studies in animals and clinical trials have shown that the nerve helps control inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, high blood pressure, and sepsis.

Devices to regulate the nerve’s electrical impulses are dependent on external monitoring. The Feinstein team developed a bioelectronic medicinal technology to measure nerve activity. An advantage of the approach is that it avoids the use of medications associated with side effects.

“We know from our previous studies that electrically stimulating the vagus nerve inhibits immune responses associated with different diseases,” Dr. Sangeeta S. Chavan, one of the study’s senior authors, said in a press release. “In this study, we establish methods to record these signals transmitted in the vagus nerve,” she added.

The team used the new technology to measure electrical activity in mice’s vagus nerves. Their work included looking for alterations in nerve activity when the mice were fed, subjected to a bacteria, or put under an anesthetic.

Their method was more sensitive at measuring nerve signals than other approaches, they said.

The new approach is “a useful tool to further delineate the role of vagus neural pathways in a standardized murine [mouse] disease model,” they wrote.

“Our new methodology allows us to begin developing ways to decode the nervous system in such a way that we better understand how to detect and regulate inflammation,” said Dr. Harold A. Siverman, the study’s first author. “We can use this new understanding to develop devices that simultaneously diagnose and treat disease.”