Pregnancy-associated Changes in Gut Microbiota May Contribute to Lupus Exacerbations, Mouse Study Suggests

Written by |

Changes in gut bacteria, or microbiota, during pregnancy and lactation can shift the immune response towards a more pro-inflammatory state that can bolster autoimmune responses and worsen lupus, a mouse study suggests.

Pregnant and lactating mice were found to have increased production of inflammatory mediators and dampening of anti-inflammatory responses, alongside worse disease, with poorer kidney function and spleen enlargement.

The study, “Pregnancy and lactation interfere with the response of autoimmunity to modulation of gut microbiota,” was published in the journal Microbiome.

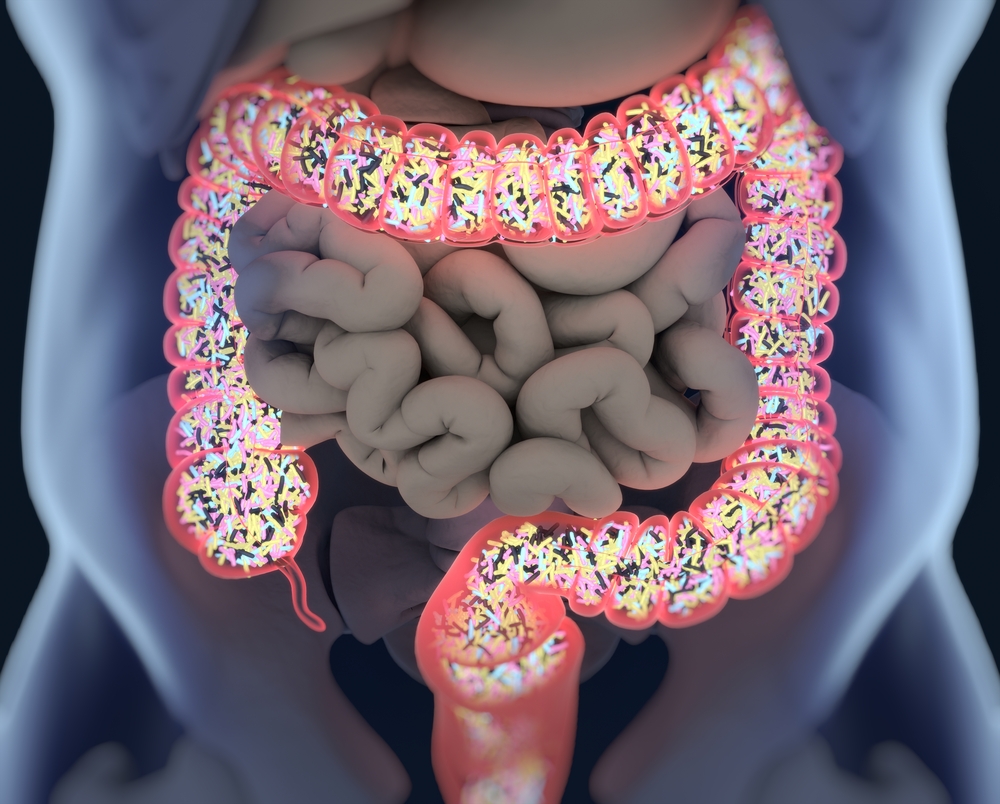

Imbalances in gut microbiota, or dysbiosis, have been observed in different autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Pregnant women with lupus have a higher risk of lupus flares post-delivery but the connection between this risk and changes in gut microbiota have not been investigated.

To support fetal development during pregnancy, a woman’s body goes through many changes — hormonal, immune, and metabolic. Researchers have seen an association between pregnancy and autoimmune diseases, but apart from hormonal effects, the reasons for that link remain unclear.

By studying mice models of lupus, a team led by researchers at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine found that the gut microbiota’s composition and diversity change during pregnancy and lactation (postpartum period), and these changes were associated with immune alterations and worse disease outcomes.

The team previously saw that treatment with vancomycin, an antibiotic that fights bacteria in the gut, greatly reduced lupus severity, so they investigated if the antibiotic had the same protective effect in pregnant mice.

However, instead of being beneficial, vancomycin aggravated lupus symptoms postpartum, which included kidney malfunction and spleen enlargement.

Those negative effects seemed to be caused by weaker immune control mediated by regulatory T- and B-cells, which play a central role in suppressing autoimmunity, along with an increase in interferon-gamma (IFNγ), a pro-inflammatory signal.

In contrast, mice that were not pregnant or lactating did not have these changes.

To investigate the underlying changes in microbiota, the researchers looked at the type and abundance of gut bacteria in vancomycin-treated animals. Pregnant and lactating mice were found to have lower total bacterial load, but increased levels of a particular species, Lactobacillus animalis.

The researchers gave oral preparations of L. animalis to mice to investigate if increased levels of this bacteria was the cause of lupus worsening. Confirming their hypothesis, the scientists found that L. animalis recapitulated vancomycin’s effects in postpartum mice, and worsened the mice’s lupus.

They went further and found that L. animalis acted by inhibiting the blood enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, which is an immune modulator seen as beneficial in autoimmune diseases. As is the case with vancomycin, this inhibition was accompanied by a greater production of IFNγ and a lower number of regulatory T-cells.

Therefore, a common mechanism was observed between vancomycin and L. animalis experiments where gut microbiota within the postpartum period shifts the immune system to pro-inflammatory responses, leading to lupus exacerbation. The results from both experiments cannot be explained by a loss of intestinal barrier function, or a leaky gut, which is known to occur in patients with lupus.

These initial findings suggest that changes in the gut microbiota during pregnancy and lactation contribute to lupus worsening.

“The ultimate goal of our research is to identify beneficial as well as pathogenic [disease-causing] gut bacterial species and to develop therapeutic strategies that are able to modulate the gut microbiota community towards a beneficial effect,” the researchers wrote.

For patients with lupus, diet and probiotics may potentially improve disease management by modulating their gut microbiota.

“However, it is challenging to achieve this goal due to the complexity of the disease pathologies, the complexity of gut microbiota, and the differences of gut microbiota communities among individuals,” the researchers said.

Moreover, further studies are needed to confirm if these preliminary findings translate to women with lupus.