Abnormal Gut Bacteria May Participate in Lupus Disease Activity, Study Suggests

An abnormal mix of bacteria in the gut, particularly increases in the bacteria Ruminococcus gnavus, may play a critical role in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a study shows.

The study, “Lupus nephritis is linked to disease-activity associated expansions and immunity to a gut commensal,” was published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

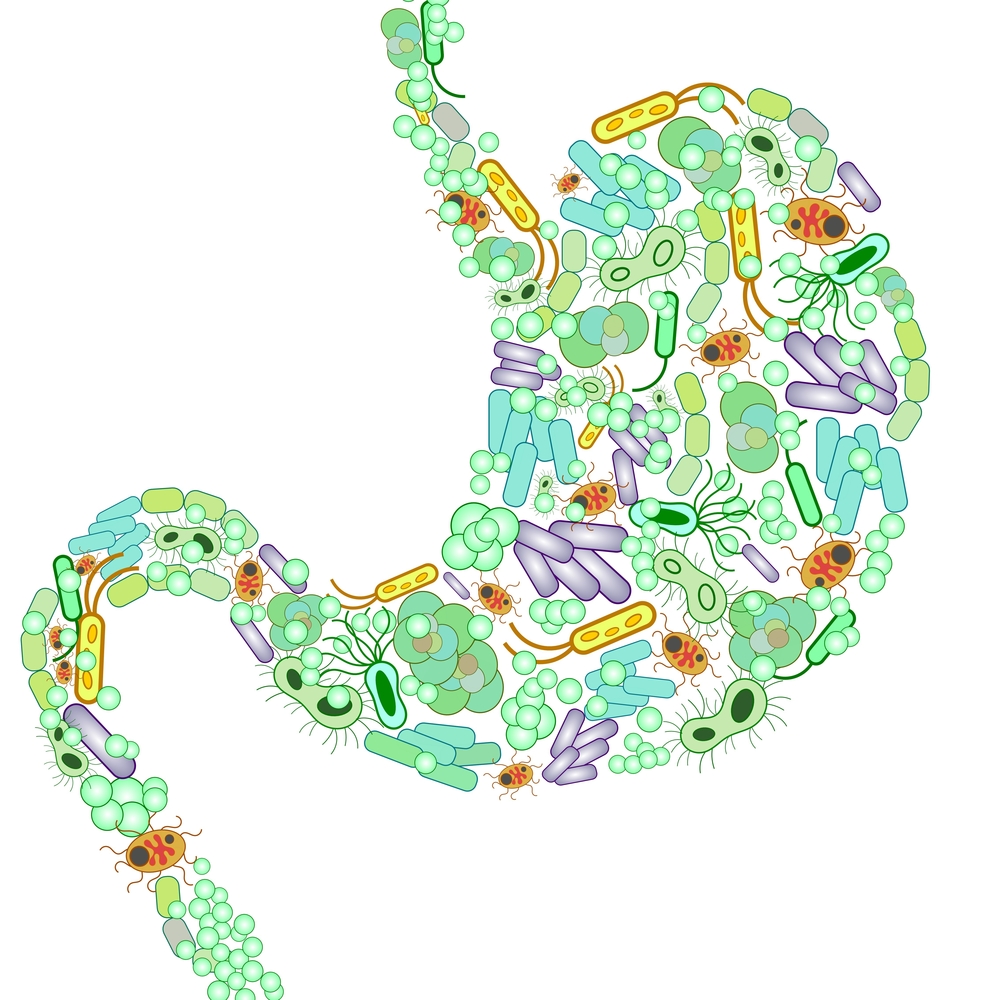

The bacteria that live in your gut — called the gut microbiome — are an odd sort of biological paradox. These bacteria are essential for a healthy life — in fact, you can’t live without them — yet the body’s immune system is designed to identify, target, and destroy bacterial invaders. Figuring out how gut bacteria do or don’t interact with the immune system to cause or prevent disease has become something of a hot topic for researchers.

Since SLE is caused by autoimmunity — deregulation where the immune system starts attacking healthy cells in the body — investigators wondered whether the gut microbiome might be involved in lupus.

To test this, the researchers collected samples of blood and feces from 61 female patients with SLE (which is much more common in females), as well as from 17 healthy volunteers who were similar in terms of age and race.

Using the fecal samples, the investigators performed a technique called 16S rRNA analysis, which basically allowed them to identify the bacterial species present in the samples.

Intriguingly, SLE patients had, on average, five times more of the bacteria Ruminococcus gnavus than the healthy volunteers. Further investigation revealed that higher R. gnavus levels correlated with disease flares.

Additionally, the investigators looked for antibodies targeting R. gnavus in the blood of the SLE patients. They found that the level of these antibodies correlated closely with SLE disease activity index scores, and patients with kidney flares had particularly high levels of these antibodies.

This is particularly noteworthy because — at least in theory — there shouldn’t be much of a need for an immune response against R. gnavus, which usually can live harmlessly in the gut.

More detailed analysis of these antibodies found that they targeted parts of the bacteria’s cell wall. The researchers speculated that this might mean bits of the bacteria in the gut are breaking off and getting into the bloodstream, where they trigger immune activity. However, this is still largely speculative, and additional studies will be needed to confirm whether this model has any clinical value.

It is, of course, just as possible that autoimmune flares in SLE alter the gut environment somehow to promote the growth of R. gnavus, rather than R. gnavus triggering SLE flares, since the researchers at this point have only found a correlation, and causality hasn’t been established yet.

Still, the researchers are hopeful that their finding will pave the way for further studies to clarify exactly how the gut microbiome affects SLE progression.

“Our study strongly suggests that in some patients bacterial imbalances may be driving lupus and its associated disease flares,” Gregg Silverman, MD, an immunologist and one of the study’s senior investigators, said in a press release. “Our results also point to leakages of bacteria from the gut as a possible immune system trigger of the disease, and suggest that the internal gut environment may therefore play a more critical role than genetics in renal flares.”

The researchers have suggested that, if their model is confirmed, it could pave the way for new treatments strategies for SLE, for example, using probiotics to control the growth of R. gnavus.